Nikolas had heard the word 'Ameriki' mentioned many times in the village. Ameriki was the land of a poor man's wildest dream, something akin to utopia, where everyone is happy, employed and rich, like his brother, who sent one single postcard to his family since he left Kambi.

When Nikolas' older brother Grigori returned to the village from Ameriki, he had enough money on him to buy 90 acres of olive trees in the village, and live happily ever after. After working in the restaurant trade for five years in New York, being the patriot that he was, Grigori decided to return to the mother country to buy the land his family could not afford to give him and to complete his Greek military service, at a time when Greece was under attack from an enemy.

"In Ameriki, people are prepared to fight for their freedom. How can I stand and watch when my country is in danger?" he replied to his family when they pleaded with him not to leave so soon after his arrival. His betrothal to a blooming village girl arranged (as befitted his financial position), he had no sooner invested his money in buying land than he left again, this time to Thesaloniki where his knowledge of English earned him the rank of officer. He managed to survive the Battle of Skra, only to die from malaria two months before the end of the campaign, having never set foot on the land that he had worked five years on foreign soil to buy. It was shared unevenly among his siblings: his four sisters received a large share each as a dowry, making them attractively eligible for marriage, while Grigori's brother ended up with the remainder, a mere pittance of the original amount.

Nikolas received 10 acres of the land that had been bought with his brother's money from Ameriki, along with the beautiful bride his brother never married. He married her out of pity; even though her engagement did not constitute a marriage (there was no marriage to consummate in the first place), she would have a hard time finding another husband after being betrothed once already. Word would have spread that she was engaged to be married; her fate had already been decided. Who knows when the next offer would come? Nikolas also felt that she had partly inherited his brother's fortune, so that she deserved to be in on his good fortune.

Aggeliki, for all her outward qualities, was not the most useful woman around the house. She had been raised in the 'mimou aptou' way, as if her beauty did not permit her to cook, wash and clean the way a less attractive woman might conduct herself with respect to these duties, lest by applying herself to such tasks, her beauty may deteriorate, fade away, disappear, as if age could never play a part in this demeaning process, and it was all to do with how often one's hands touched the soil on the ground or how much sunlight shone on a woman's face.

Nikolas' land was fruitful, especially once he had cleared most of it from the thyme and dictamo bushes, after which he set about planting it with olive trees. He hunted hares and wild birds, plentiful in his own fields, but the cook was wonting in culinary skills; the rumour spread all over the village, with its population of 500, that Aggeliki was a hopeless cook. Nikolas didn't know who to feel sorry for more: himself for earning such fate, or the oven-charred or water-sodden carcasses that came out of the kitchen, sometimes sporting their fur or plumage. When he sat at the kafeneio with other men from the village, and listened to their chatter about how their own wives conducted themselves at home, his gut tightened.

"Give her time, Nikola, you're not even into a year of married life," the others would comfort him. But he neglected to tell them that Aggeliki entered the marriage in this way right from the start, and that his clothing was now almost ragged and Aggeliki showed no sign of replacing them for him before they had become tatters. He felt that the land - and possibly Angela's inviting appearance - had cursed him into the misfortune of a loveless marriage.

*** *** ***

When Aggeliki became engaged to Grigori, she had hopes of leaving the village for good. She knew that Grigori had made a lot of money, but she didn't realise that he had invested it in the mountainous territory that made up the village of Kambi. She expected that, once he had finished his military duty, he would move to lower ground - as most villagers who prospered did - and build a suitable dwelling for them to live in. After all, this is what he must have been accustomed to living in in Ameriki; everyone there apparently lived in fully furnished houses and had their clothes made for them by tailors and seamstresses. They did not need to shear sheep, spin yarn, or weave cloth on the argalio, which would eventually be turned into bedsheets and men's shirts; like cooking, sewing was not Aggeliki's forte. So it was to her greatest disappointment that Grigori did not return from Thesaloniki. She knew what fate had in store for her.

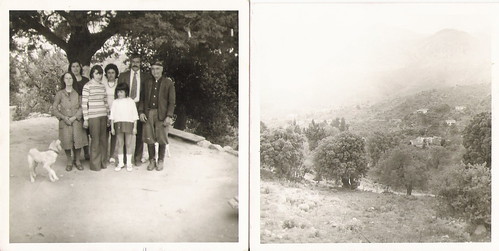

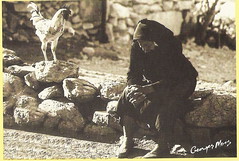

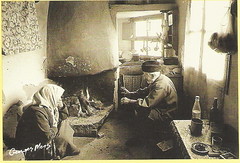

(Crete in the 1960s, four decades after Aggeliki and Nikolas emigrated; the photos come from CRETE 1960, by John Donat, Crete University Press)

Aggeliki had not wanted to marry her fiance's brother, but there was no question of that now that Grigori was dead. Had she been married to Grigori before he had left for Thesaloniki, she would have inherited his land, a mixed blessing if ever there was one. She would have become a rich woman, highly ineligible for marriage; what man in the village would have been able to match her wealth? As it was, she suffered the cruel fate of being labelled a widow after Grigori's death anyway, even though she had never married; such was the nature of life in the impenetrable snow-capped mountains of Kambi, at the foothills of the Lefka Ori.

She looked around the house Grigori had built in roughshod style a short while before they were married: two simple stone-built rooms with openings for windows, blocked by wooden shutters to stop the winter cold from entering. There was an outhouse a little way from the house and an earth oven built next to one of them rooms. This was not the Ameriki she had dreamed of, nor was it the town of Hania that she had hoped to move to after her marriage. It was true that she had never known better than the village life she was born into, but no one could stop her from dreaming, which is what she did most of the day when Nikolas was away, clearing scrubland, planting olive trees, hunting hares and grazing sheep.

*** *** ***

Kambi, 1921

Nikolas was sitting at the kafeneio. He usually sat on his own these days, as he had little to share with the locals. It was almost three years since he married Aggeliki and still no children. He had by now grown accustomed to the way the kafeneio chatter died down when he entered the shop, and the compassionate smiles of the other men sitting in groups around the tables. He picked up one of the newspapers that had been left on the fireplace, to be used for kindling a flame. Although he had not finished primary school, his reading was at a reasonable level. He did not write anything apart from his name; there was no one to write to, in any case, and no one interested in reading anything that he wrote.

He had not grown tired of working the village land. What tired him most of all - and he seemed to have aged a decade since his wedding day - was that he was working with no future in mind. So what if he had thousands of olive trees; so what if his coffers were filled with olive oil. There was no one to eat it, and no one to sell it to; people were too poor in the village to buy more as their own stocks ran out, so they simply used it more sparingly. The economy of the country was still engaged in a new war effort; there was no interest in trading olive oil. So much effort for very little reward; produce-rich but lacking currency.

Every morning started off the same, as every evening finished. Routine after routine, with very little variation. Nikolas saddled the donkey, which lived in a makeshift shelter next to the main house, along with a group of six goats and sheep which Aggeliki milked each morning, and left for the hills. The land he had inherited had never before been touched by human hands. He worked most of the day with some paid labourers clearing the land of the scrub wood and rocks, digging it up, tilling it, and planting it with olive trees. Aggeliki had filled a woven bag with bread, some olives, a chunk of graviera and a carafe of wine for Nikolas to curb his hunger, before he came back home at midday. It was usually too hot to work after that; the sun did not rest even in winter. The midday meal was a very silent affair, one that always heightened the void between the couple. They could not fill the space between them with their presence. They had little to say to each other; their world had become static.Without offspring, there was no one to work for but himself, and his wife, of course, who, at times, seemed to live in her own reticent world. Apart from his requests for better food and clean clothes to wear, he had very little to say to her. Yesterday, she had cooked youvarlakia in a tomato sauce, using the anidres tomatoes he had hung on the rafters of the house to dry for the winter, while the lemon tree was bulging from its own weight, laden with fruit. Hadn't she ever had youvarlakia? Didn't she know how to make an avgolemono sauce?

"What were you thinking, using the tomatoes I was saving for the winter? Where are we going to find them when we need them, woman!" He could hear the rumble in his own voice as he shouted at her. Usually the house was so quiet. He wasn't used to hearing himself speak like this. He left the house feeling more angry with himself than his wife.

Things were not looking good in Smyrna: according to the front page, war was imminent. His mind immediately conjured up the image of his brother leaving the village to fight against the Bulgarians. What was it that his brother had said? "In Ameriki, people are prepared to fight for their freedom. How can I stand and watch when my country is in danger?" Did he understand what he was fighting for? Had he thought about whether the cause was worth fighting for? Did he know how close the war was to the end when he lay sick and dying? Nikolas did not share his brother's patriotism. He did not want to fight a war that he hadn't started. He did not wish to be one of the victims of war like his brother. Now seemed a good time to leave the village, maybe even the island, and why not the country if it got to that stage. The shame of childlessness could be avoided if he simply lived elsewhere, far away from anyone who knew him. Nikolas put it in his mind to seek a passage to Ameriki.

*** *** ***

The video shows how Cretan families from Kambi were living in California in 1948; Crete at that time was extremely poor, while Greece was in the midst of a civil war. To the average Cretan, this picture would have seemed like a scene from paradise; poverty remains the main reason why, up to the early 1980s, Greek people emigrated to the New Worlds.

This post is dedicated to all the Cretans from Kambi, my mother's village, living in Modesto and Manteca, California, where very many of them congregated. It doesn't matter where they were born, whether it was in Crete or America, or whether they continue to speak Greek or not; they are still Greek at heart, and they know it.

©All Rights Reserved/Organically cooked. No part of this blog may be reproduced and/or copied by any means without prior consent from Maria Verivaki.

wonderful story and tribute to Cretan families from Kambi.

ReplyDeleteas for my non comment post i did it on purpose. thank you.

beautifully narrated... you are a super story teller!

ReplyDeleteby the way did nikolas ultimately migrate to ameriki?

Great story and excellent pictures. I love to see the Cretans wear the traditional clothes.

ReplyDeleteGreat, great story well presented. Gorgeous photos. Thanks Maria for sharing!

ReplyDeleteYou seem to have the gift of story telling, MK. I'm really interested to know how this all turns out.

ReplyDeleteBeautiful story and moving pictures.

ReplyDelete