In the globalised world that we live in, it becomes an unavoidable necessity to buy goods that have been imported. It has long been recognised that

ASIA is more than willing to produce products that all countries right around the world can import cheaply, while the wholesalers can still make a reasonable profit selling them off to consumers at an equally cheap price. This is the commercial curse of modern times. If you want to buy something that hasn't been manufactured in Asia, you have to pay considerably more for it.

This is probably where this little coffee and saucer set took its first steps, in a factory somewhere in Asia. Hundreds of thousands of these white demi-tasses were probably made in a a noisy dirty factory, by underpaid overworked employees of rich and powerful businessmen who had people in the right places to turn a blind eye to the working conditions their employees were subjected to. It's hard to imagine what kind of injuries they might have sustained to produce these ornamental cups and saucers. A stack of badly stored boxes may have crashed onto someone's head; maybe someone else suffered first-degree burns by improper handling of the pottery in the kilns.

Nevertheless, this little coffee cup and saucer, appropriately decorated with a map of the island of Crete, travelled intact to

EUROPE, eventually making its way down to Hania, on the island of Crete. Knowing the Greek authorities, it's not difficult to imagine the Cretan cups ending up in Kerkyra by mistake, or the Kerkyra ones accidentally being sent to Crete. These ones made their way to the souvenir shops of Stivanadika, where most tourists buy their souvenirs from: T-shirts, old-fashioned summer dresses, handmade leather sandals, I-love-Crete keyrings, gold jewellery fashioned in Cretan-inspired designs, olive oil soap, mugs, tea-towels, among a host of others. Cups and saucers always comes in 6-packs; it must have had another five siblings, all packed in the same box, waiting to start a life in a person's home.

*** *** ***

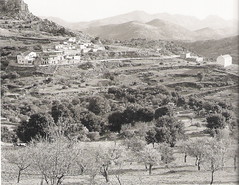

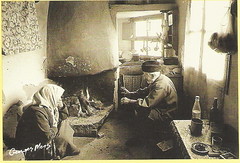

The Daughter of a Poor Farmer had been born into a poor agricultural family in a village in the foothills of the Λευκά Όρη (Lefka Ori - White Mountains) of Hania. She would have liked to go to school - there were 150 children enrolled in the village when the second world war broke out - but this was impossible. After second grade, she didn't attend much at all; there were more important tasks to be done. One of the easiest for a young girl her age was to lead the family's cows to a grazing field every day and milk them. By the time her tasks were completed, while her mother looked after her four younger siblings, there was just enough time to clean up and tidy the two rooms where the family lived: one room for the humans, and another for the animals.

As she left childhood and entered adulthood (there was no such thing as adolescence in those days), she began helping her mother carry fresh produce to Hania, where they would sell or exchange them for products they didn't produce themselves: rice, sugar, coffee, coloured thread for the rugs she made on the αργαλειό (argalio, weaving loom), buttons for shirts. They would start walking in the afternoon with the donkey laden with goods, and keep walking until it was very dark. There was a spot in the mountains which was sheltered and they overnighted here, sleeping on the ground. In the early morning, they'd wake up and continue on to the road for Hania, in order to get to the market to do their trade. After the days' work was over, they'd make their way back up again, stopping in the same place. The journey was more difficult this time, as the walk was uphill, getting steeper and steeper as they walked back up. They could only ride the donkeys if they had not once again been loaded up with more goods.

Although her family had a few patches of earth of their own, they did not have many olive trees to produce the amount of olive oil that their family used; five adults and two parents needed about 200kg of olive oil a year, especially if the main form of sustenance was

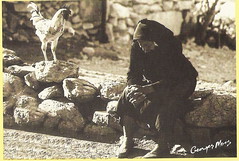

psomi me ladi. The Daughter of a Poor Farmer became a μαζώχτρα (mazohtra), an olive picker for other wealthier families. In those times, olives were left to fall on the ground, and were then picked up, one-by-one, with the pickers' backs bent the whole time. Either they were collected into large baskets, or they were thrown onto large sheets. (Technology, as well as the black plastic netting that is now used to collect olives that drop onto the ground, took a long time to get to the mountainous villages, by which time, rural life had suffered a decline.) From this job, she was given a small share of the crop to take home with her, after it was ground into oil.

She had by now reached the age of 30, but she was so poor that she was never considered a worthy bride. As the oldest child in a family of five, this spelt doom for the family: if she didn't get married first, then the girls next in line would also have the same fate. Eventually, the family had enough oil to cover their needs from the girls' work, so The Daughter of a Poor Farmer asked to be paid in money instead. She worked with a bent back one whole olive season and dreamed of what she would do with the first real cash that she had received in her life.

All spring, she waited patiently to be paid for the work she had done all that winter, but the money didn't seem to be coming forth. There being no telephones in those days (no electricity, let alone phone lines!), she had to walk to the olive press herself to find the owner and ask him for her pay. She put on her best clothes and the only pair of shoes she had, which was quite clean, since shoes were never worn in and around the house when work was being done. They were saved for 'good' days.

The Daughter of a Poor Farmer entered the olive press. No one paid any attention to her, even though no one was doing any work in particular at that moment. She asked someone about being paid by The Rich Landowner for her last olive-picking season's work.

"Φαλίρισε (falirise)," was the one-word reply she got.

"What does that mean?" she asked.

"Φαλίρισε," the man repeated without looking at her. "He's got no money to pay you with. The bank's repossessed all his assets."

The Daughter of a Poor Farmer returned home and told her parents what she had learned. All that work for nothing, fake promises, false aspirations. If this was life in the village, they were resigned to poverty, and all because The Daughter of a Poor Farmer was still unmarried. It was at about this time that an announcement went up near the community offices about a paid passage to a relatively new country in

AUSTRALASIA, offering the opportunity for women to work as cleaners and cooks, in return for a small salary which they could save and a paid return trip to their homeland. They needed to stay for two years in the job that they were offered, and there would be a training period in an institute in Athens where the girls would be offered English lesons and basic training in the service sector. To The Daughter of a Poor Farmer, this sounded perfect, even though she had no idea where she was heading to.

*** *** ***

The Daughter of a Poor Farmer was assigned as a chambermaid in a boys' agricultural boarding institute. She cleaned the rooms and kept the lobbies clean. The work was not very difficult, but the hours never seemed long enough. Once work was over, there was nothing to do, nothing at least for The Daughter of a Poor Farmer, who was not used to going out on the town, drinking alcohol in pubs, meeting up with the opposite sex. Imagine if her parents found out where she was now: how could she prove to them that she did not carry on as the other women did? They were all from the same island, but for the first time in her life, The Daughter of a Poor Farmer wondered whether she had anything in common with her compatriots.

The institute housed its own church on the premises. The Daughter of a Poor Farmer was invited to attend the church service, along with the other employees. She accepted the invitation. As she entered the church, she wondered why there were no icons on hanging on the walls, like in the Greek Orthodox Church that she had been raised in. No one seemed to be making the sign of the cross. Even if she wanted to do so, she couldn't understand what the priest was saying, and where was his petrahili? She looked at the pale faces of her employers and the dark faces of the young male pupils, and wondered what she was doing in their church. She felt that she did not belong here. The thought suddenly struck her that were she to die here, there would be no place for her to be buried, because there was no Christian Orthodox church. She suddenly felt very alone, and the two year-contract now seemed to her a long way away.

*** *** ***

The people at the institute were very kind to all their staff. They knew that the Greek girls wanted to see the other girls that they had travelled with, most of whom eventually settled in the Capital City. The Capital City had a Greek church in the centre of the city; wherever there is a Greek church, there are Greek people, and wherever there are Greek people, the Greek language will be heard. The Daughter of a Poor Farmer had met many Greek people in the Capital City on the day trips that the institute organised for their foreign workers. At the end of her contract, she decided to move there, instead of going back to the island. Sofia and Tasos, islanders like herself, had befriended her. They liked her so much that Tasos declared: "I'm going to find you a husband from the island." And that would end the blight on her family: the stigma of the unmarried eldest daughter.

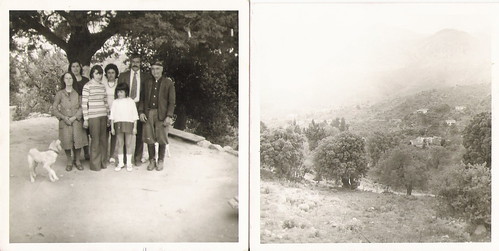

From The Daughter of a Poor Farmer, she was transformed into A Successful Immigrant with a faithful husband and university-educated children. She still longed for the island, and went back to visit her sisters and their husbands and their children as often as possible, but she could not change the fact that her heart was on the island, but her home was thousands of miles away. Every time she visited her homeland - it was getting harder to do that as the years went on - she bought a trinket to remind her of the place where she was born. One of her favorite souvenirs was a set of demi-tasse coffee cups with a picture of the island. She kept them as far away from dust as possible, in the confines of her elaborate wall unit in the lounge which she opened up on just a few days a year - you could count them on the fingers of one hand: Christmas, Easter, her nameday and her husband's nameday; the children were by now celebrating their own namedays in their own homes. But the demi-tasses with the island motif were her favorite coffee cups, and she always served her guests Greek coffee in them, even if they didn't take it in the formal room where the cups were kept.

*** *** ***

"Talk about a hoarder. How many coffee cups can a person own?"

"Do you think they have any resale value?"

"Let's organise a garage sale."

"Do charity shops collect?"

The children of the Successful Immigrant had all been back to their parents' homeland at some point in their lives. They all had fond memories of the place where their parents were born, where they had spent a few winter holidays when they were young, before their grandparents had died. Since then, they never really felt any attachment to the island, since their last direct link had away, and they all had lives of their own in the New World, which had now become part of the globalised universe that the Earth had turned into.

The Youngest Daughter of the Successful Immigrant had herself moved to

AMERICA, where she was recently called from on her mother's passing. She had never been a supporter of her mother's hoarding excesses, always berating her for spending money on yet another useless dust-collecting trinket, but when she saw the coffee cups with the picture of the island plastered across them, her mind flooded with memories of her parents, her grandparents, the village house, the souvenir shops, the blue sky, the golden sand of the beach, the light lunches at the tavernas that she had enjoyed under the shade of a tamarisk tree, her first love. It suddenly occurred to her that her mother had sacrificed her entire life to give her family a better opportunity in life, all the while living her life in an adopted homeland. She looked around the lounge, the most under-used room in the house she was brought up in with a twenty-five metre hallway, and everywhere she saw Crete: on the wall as an embroidered hanging, on the glass door as a sand-blasted picture, on the coaster set on the nested tables, in the tablecloth of the dining room table, in a faded postcard that her aunt had sent, now long gone herself, all signs that her mother had been living a temporary life in the New World with a permanent sense of home in the Old World, the lounge being transformed into a mausoleum of Crete.

The house was emptied of its contents and sold to a new owner, a property investor, who planned to turn it into four self-contained apartments, the latest fashion for old inner-city houses. After the expenses were paid, the inheritors all received their share of their parents' estate, and The Youngest Daughter was now free to go back to America, the place she now called home, her suitcase packed carefully so as not to disturb the demi-tasse coffee cups nestled safely in amongst her clothing. They would now start a new life in a new wall unit in a new house in a new country, where people would constantly ask The Youngest Daughter about the history of these cups, where they came from, and how she acquired them.

©All Rights Reserved/Organically cooked. No part of this blog may be reproduced and/or copied by any means without prior consent from Maria Verivaki.

The white sign below the display window says:

The white sign below the display window says: