The image of Athens that springs to mind in most people's heads is that of a tightly packed sprawling treeless city full of apartment blocks that bear a resemblance to the notion of inhabitable accommodation, with the pride and centrepiece being the Acropolis. The image is generally correct, but this did not resemble my first introduction to the city that the Scottish like to think compares to their very own Edinburgh (and why a sun-starved city like Edinburgh should, only the Scots can tell us - it's all Greek to me). As a Greek born abroad, I had very little idea what there was in Athens beyond the Parthenon. The leafy northern suburbs (like Kifissia) and the southern coastal suburbs (like Palio Faliro) were and still are unknown to me, despite having lived in Athens for nearly four years. I went to the wild west, into an area that remains relatively unknown to most of the tourists and locals alike; you don't go west of Athens unless you need to.

When I first arrived in Greece, my very first introduction to Athens was spent in an area that was very far removed from the images of the Athens that I thought I was coming to, a mental image acquired from the tourist brochures at the travel agencies, the travel books in the Wellington public library, and the postcards we were occasionally sent from our relatives. Everyone there lived in single story dwellings, there were quite a few parks and many open spaces surrounding the houses, and the Acropolis was regarded as one of the most useless rocky hills on a prime spot of land in central Athens. The area was close to the sea, hence the name given to the region: Παραλία Ασπροπύργου (Paralia Aspropirgou: the Aspropirgos coast).

Aspropirgos is located 17 kilometres west of the centre of Athens. Many members of my mother's family moved to this area from the village of Κάμποι (Kambi) in the 1960s, in search of work and better opportunities; generally speaking, they were aiming for a chance to improve their lives. In the poverty of the post-war era, with the demise of village and rural life, everyone was leaving the agricultural regions and moving into the urban environment. But in Paralia Aspropirgou, urbanisation never seemed to catch on at the rate that it had in the centre of Athens. The area only recently acquired footpaths and tarmac on the road, while the main form of grocery shopping is still the neighbourhood παντοπολείο (pantopolio). Everyone knows each other; they are often related to one another in some form, be it as a sibling, best man, godparent or the same village origins. Many people from Crete settled in this area, creating enclaves of Cretan communities, in the same way that immigrants to the New World did in America and Australasia.

My aunt was one of those 'migrants' who settled in Aspropirgos with her young family after her husband was 'excused' from his duties as a policeman (due to the curse of the bottle). There were many job opportunities available in the area, all within walking distance of the first dwellings in the area: makeshift roughshod container style houses, onto which rooms were added one by one, until they were big enough top house all the occupants. They usually contain two bedrooms, and resemble brick and mortar shacks. The area was classified as residential only recently; since then, pavements and tarmac were laid on the roads, which were also given street names. Eventually, Thia bought her own home, very similar to the one she rented when she first came out to the area. It still remains a simple house, although it has been modernised to the point where she has air conditioning in the summer and radiators in the winter. Her tiny garden contains an olive, a lemon and a walnut tree, all of which she planted herself.

(the footpath, tarmac and street names are relatively recent additions to Paralia Aspropirgou)

(the footpath, tarmac and street names are relatively recent additions to Paralia Aspropirgou)"When we moved up with Leonidas-God-rest-his-soul, I realised that we would never move back down to Crete. Because of the jobs. Because we had no work there. It was very tiring travelling to Crete and back during the olive season, so I sold the olive grove I had been given as part of my dowry. What use was it to us? We had jobs here, and our lives were based here. I bought my own home with the money from the sale, and helped my daughters into theirs."

So what kind of jobs did everyone do around here? Factories. Hundreds of factories. Light industry, heavy industry, shipbuilding yards, gas works, electricity plants, metal works, oil refineries, cement works. The different suburbs of Paralia Aspropirgou weren't named after a church, in the classical Greek manner; they were all named after the works close to it.

Ask a cabbie to go west of Athens beyond Egaleo and watch the reaction on his face.

"Where ya goin' to,

kiria mou?" asked the taxi driver.

"Paralia Aspropirgou," I replied. His face scrunched up; Paralia Aspropirgou isn't the most popular destination for cab drivers - there's no guarantee of a return fare. It's like World's End, the point of no return.

"Know ya way round there?" he looked at me suspiciously.

"Sort of, you can drop me off at Halips."

(Halips factory, as seen from the entrance to the suburb of Paralia Aspropirgou)

(Halips factory, as seen from the entrance to the suburb of Paralia Aspropirgou)Halips (ΧΑΛΥΨ) is the now defunct cement works across the road from what looks like a narrow insignificant side street

on one of the filthiest motorways in Europe, the very road that one must take to go from central Athens to Corinth. Looking at it from the motorway, it is difficult to imagine that there is sense of home and hearth behind the putrid dust storms that Halips left behind well after it closed down. Not a single house can be seen from the main road, only industrial plants. It looks like Hell, a wasteland of metal, concrete and glass, right next to the coast, a site probably chosen for the ease with which waste could be dumped without anyone needing to find out (toxicity tests started being conducted well after the environmental damage had turned the area into Athens' biggest sewer). Nothing shines here on the main road. If you saw the metal works in the Lord of the Rings films, you can conjure up the right picture in your mind. The windows are permanently covered with a thick film of dust, which doesn't get thicker because it is so dry, nothing can stick onto it any longer. It blows around continuously, entering the houses, settling on the ground, piling up in corners.

(when you don't have a choice, you may indeed decide to go for a dip here; don't worry about the mass of ships ramming into you - this is a ship cemetery, they're not going anywhere)

(when you don't have a choice, you may indeed decide to go for a dip here; don't worry about the mass of ships ramming into you - this is a ship cemetery, they're not going anywhere)On my first night there, I woke up in the middle of the night feeling somewhat disoriented, as is common when you stay in an unfamiliar place for the first time. From the window of the kitchen-cum-dining room where I slept, I saw a fire that seemed to be burning on the top of a chimney. I startled my aunt.

"Thia, wake up! Something's burning!" I pointed to the window. She turned to look at me, with a surprised look on her face, then looked back out the window without saying anything.

"What's that fire there?" I realised that she had seen this flame before.

(look closely; you'll see the Olympic flame, too)

(look closely; you'll see the Olympic flame, too)"Oh, that's the Olympic flame," she replied, and returned to her bed. "Διυλιστήρια (

thilistiria - oil refineries)," she added. "Nothing to worry about."

I received a few more shocks over the next few days of living in Paralia Aspropirgou. One of the most shocking for me was that nobody could direct me as to how to get to Athens. No one knew how to go to the Acropolis. I finally found out from someone who had been living in Paralia Aspropirgou for a long time, and worked in Athens.

(the original Halips bus stop was at the point where the iconostasis is now; don't kid yourself about why the bus stop was moved a few metres away just below the recently built overpass )

(the original Halips bus stop was at the point where the iconostasis is now; don't kid yourself about why the bus stop was moved a few metres away just below the recently built overpass )"Cross the road and stand outside Halips. All the blue and white buses that pass this road terminate in central Athens (except one which clearly says PIREAS on its ticker tape). Buy your ticket at a kiosk before you board the bus and validate it once you get on. On a Sunday, getting into Athens takes a quarter of an hour from here, since there's less traffic."

It sounded surprisingly easy. "Why couldn't anyone else have given me this information?" I asked her.

"Oh, don't ask anyone anything here. They don't know, really they don't know

anything. In any case, they do their shopping in Elefsina, which is only a few kilometres from Aspropirgos. It's much more convenient than entering central Athens. They'll just get lost, believe me, they'll never be able to return home if you let them loose there."

(various views of Iera Odos; heading westwards, once you pass the signpost for the old monastery, the road loses its tree-lined scenery and takes on a deserted ghostly appearance)

(various views of Iera Odos; heading westwards, once you pass the signpost for the old monastery, the road loses its tree-lined scenery and takes on a deserted ghostly appearance)

Elefsina, 5 kilometres westwards of Aspropirgos, is where

the site of the ancient sacred mysteries perfomed in the goddess Demeter's honour are located. The site was highly significant in the ancient world, with members of her sect being sworn to secrecy about the ceremonies held there. The road from Eleusis (as it was then called) to Athens was known as Ιερά Οδός (Iera Odos), the Holy Road. It is still bears that name - Iera Odos offers some of the most pleasurable shopping opportunities in Western Athens - one big long stretch of road with few turns and bends, leading straight to the Parthenon, although this will not be so obvious any longer, what with the reshaping of the city of Athens once the urban sprawl began to spread out of control. There was a time when the Acropolis could be seen right along Iera Odos, although this has changed too, since the construction of tall buildings, obscuring the view of the hill where the Parthenon stands. My father remembers seeing it as he walked to work at the Pitsos appliance factory in Egaleo. It is more visible once you pass the site of the Agricultural University of Athens, which coincidentally is located in the most polluted area of the city, the western suburbs.

*** *** ***

So what did Little Crete have to offer in terms of edibles? I recently overnighted at my aunt's house, before meeting up with a friend who I had never met before in my life.

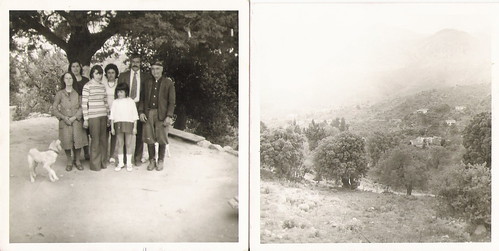

(typical views in the area of Paralia Aspropirgou)

(typical views in the area of Paralia Aspropirgou) "So what brings you to Athens, dear?" asked my aunt.

"I'm going to meet up with a friend who I've never met before," I answered.

"Oh.. well.. you know what you're doing, you always did." We left it at that.

"Are you hungry?" she asked me. I had left my own home in Hania at 7pm, and it was now half an hour before midnight.

"No, not really, Thia."

"I've got some leftover rabbit from today's lunch," she tempted me, an offer I couldn't really refuse. "I've cooked it with pasta, and there's just one more serving of it."

Thia comes once or twice a year to Hania and stays with her brothers. When she returns to Athens, she takes whatever she can in terms of fresh produce back with her. Cretan products are not always difficult to source in Elefsina - her main shopping area - but they are not always available when she does her weekly shop. Her brothers give her freshly slaughtered rabbits and chickens, farm fresh eggs, potatoes and whatever is in the garden at the time of her visit. There are also some Cretan supplies stores in Elefsina. A very small laiki street market runs weekly in the area, mainly used by old people and those that do not own a car. Most people drive to the large well-stocked supermarkets in Elefsina to do their shopping.

"I almost forgot, Thia, I bought you some aubergines and peppers." She was most thankful; we discussed different recipes I cook to use up the

eggplant surplus in our garden.

It was time to go to bed. Thia doesn't usually stay up so late. She did it for me. As it was a warm night, we left the window open in the bedroom. It was eerily quiet in the neighbourhood, save for a humming sound. This sound did not stop, in the same way that the Olympic flame never blows out in the Aspropirgos refineries. It was the sound of the humming machinery that was working 24/7 in the surrounding area, a slow buzz that did not so much interrupt the silence, as much as pervade the air. Every other sound was like an over-write on the silent humming, like the lyrics to the refrain of muzak playing in a supermarket, an artifical world where nothing seems to change. Paralia Aspropirgos had not changed much at all, despite my first visit to the area being seventeen years ago.

In the morning, Thia insisted that I have breakfast with her. She brought out some φρυγανιές (

friganies - dry toast squares), feta cheese made in Hania by a local cheesemaker ("ask your uncles where they buy it from," she informed me), and a bowl of cured olives from the olive tree on her property, served with a cup of hot τούρκικο (

tourkiko - Greek coffee, named after its origins).

"Do you like it here, Thia?" What a question; she's been living here over thirty years.

"Of course, I do, dear, it's much better to be living in a little shabby house that I can call my own, rather than the best apartment in central Athens. If I didn't live here, I'd have gone back to Crete. I could never live in a box. And it really isn't that bad here; I know everybody and we all look out for each other. At night, all the lights from the factories sparkle like a Christmas tree. It's really quite beautiful."

If you could just keep your eyes away from the main road, Paralia Aspropirgos doesn't seem such a bad solution to the Greek housing and employment problem.

©All Rights Reserved/Organically cooked. No part of this blog may be reproduced and/or copied by any means without prior consent from Maria Verivaki.

Yesterday's answer: chunks of charcoal are in the big white sacks. They are produced at the end of summer, which is why there is alot available at this time, but it is mainly used for the BBQ, not to heat ourselves.

©All Rights Reserved/Organically cooked. No part of this blog may be reproduced and/or copied by any means without prior consent from Maria Verivaki.